- Home

- Emma Gannon

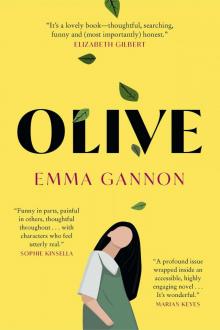

Olive

Olive Read online

Also by Emma Gannon

Ctrl Alt Delete

The Multi-Hyphen Life

Sabotage

Praise for Olive

“This tale of four young women trying to sort out the dilemmas of motherhood . . . will bring relief and recognition to many. It’s a lovely book—thoughtful, searching, funny and (most importantly) honest.”

—Elizabeth Gilbert, author of Big Magic and Eat Pray Love

“Funny in parts, painful in others, thoughtful throughout, it explores many dilemmas, with characters who feel utterly real.”

—Sophie Kinsella, author of I Owe You One and Confessions of a Shopaholic

“A profound issue wrapped inside an accessible, highly engaging novel . . . It’s wonderful.”

—Marian Keyes, author of Grown Ups

“Honest, relatable and incredibly real, Olive is going to resonate with an entire generation of young women."

—Louise O’Neill, author of The Surface Breaks and Asking For It

“Fresh, funny and utterly distinctive, and so loving and insightful about friendships and the way we grow and change within them.”

—Emma Jane Unsworth, author of Animals

“Emma Gannon’s novel raises important questions about women’s lives—important themes explored by a true champion of women.”

—Nina Stibbe, author of Reasons to Be Cheerful and Love, Nina

“An unflinchingly honest and thoughtful piece of fiction . . . In Gannon’s capable hands, women are not so much divided along their disparate lines—but united.”

—Pandora Sykes, author of How Do We Know We’re Doing It Right?

“Olive is a delicate, heart-breaking and delicious story that will bring a pang of delightful recognition to every woman who reads it.”

—Scarlett Curtis, author of It’s Not OK to Feel Blue

“Incredibly warm and loveable, you won’t be able to put Olive down.”

—Bustle

“Olive’s story is big and bright and beautiful and holds up a much-needed mirror to society. I can’t recommend it enough.”

—Lucy Vine, author of What Fresh Hell

“Cuts rights to the heart of conversations around women and the stereotypes we either adhere to—or reject.”

—Cosmopolitan (UK)

Prologue

Editor’s Letter

Published January 18, 2020

From issue 24 of .dot magazine

“The Mother of All Choices”

by Olive Stone

I am the same age as my mother when she had me. Thirty-three. If I turn my face a certain way in the mirror, I can see her looking back at me—we have the same chin, thick dark hair, and a mole more or less in the same place above our lip. But I am miles away from who she was then. We might look the same, but in all other ways we are not. I was told when I was little by my Grandmother Pearl that when you turn thirty, you are suddenly gifted a new kind of respect for yourself. “You will care less, as if by magic, my dear,” she would say. “Being young is terribly confusing. Quite awful, really.”

It’s true that as you grow older, you know yourself better. You leave bad parties slightly earlier. But then, the downsides: your bones are slowly beginning to disintegrate, a natural decline in bone mass, though consuming vegetables, protein, and collagen might help. You start to realize exercise is no longer about vanity but necessity. Your metabolism changes too, sadly starting to slow down. You start to realize you “should” go easier on the cheese boards, but you won’t because brie is everything. Then there are the hangovers! Drinking two bottles of prosecco doesn’t feel like having a beaker of lemonade anymore—it fizzes and pops and aches in your head the next day, but fortunately you have more willpower now to “get on with it.” Rumor has it your libido changes too; it ebbs and flows and tends to dry up a bit. And of course you’ll start noticing a few more lines on your forehead and around your mouth that seem to be slightly more prominent than before, but you also think it looks cool. A sign that you know more stuff. You might feel the need to chuck out your entire wardrobe and start again, to reflect a new chapter in your life, a new confidence, a new relationship with your body. You slip into your new skin like a snake that has finally come home. On the whole, things start to seem easier—plus, you have a bit more cash now. This is everything grandmother Pearl foreshadowed.

And then, bam—even though I should have seen it coming—babies are suddenly on the brain. There is an abrupt tap on the shoulder from friends, family, society, and suddenly it’s the number one topic of conversation. Babies. Babies. Babies. When. When. When.

When I was twelve, in 1999, I remember being obsessed with snipping cutouts from my mum’s old Argos catalogs and sticking them into the blank pages of my notepads. Notepads were the only present people bought me or put in my stocking because I was always scribbling as a tiny kid. I would have stacks of them: beaded ones, velvet ones, bright-pink ones, furry ones, holographic ones, and secret diary ones with a lock and key. But I had stopped writing and started making collages instead. I would neatly cut around pictures of products I found interesting from the flimsy, thin pages of Argos and glue-stick them inside the blank pages. Navy-blue patterned plates. A big wooden rolling pin. Hand-painted teacups. A garden slide. A stylish armchair. A woolen throw for the sofa. A picture frame designed for four landscape-shaped photos. I would trim carefully around each one with big kitchen scissors, in circular motions, around the plates, bowls, crockery. I would stick them into the blank pages, designing my life in detail from an early age. I believed I would have these perfect little things in my home when I was older. I would have a garden. I would live in a big house, bigger than my mum’s. I would have a husband. I would have a baby too, probably. Or two. Or three! Because that’s what you do. My friends would come ’round with their babies. They would all play together. We would go to the beach and tell them not to eat the sand, while we’d drink tea in thermoses and reminisce about the good old days. That’s what grown-ups did. When I am an adult, I would think, everything will be good. I will finally be free. Adulthood = Freedom.

I painted a picture of my Big Bright Future through the lens of an old Argos catalog, and today I am inside that distant future—in the painting, living and breathing it. But I don’t have the hand-painted teacups or the navy-blue patterned plates. I don’t have a garden slide. And I don’t have the baby either.

Looking back, perhaps the baby thing was always more of a blurry idea—one that I could never totally zoom in on. I could only really imagine it hypothetically. The idea of becoming a mother was something passed down to me—from my mother, and her mother’s mother, over centuries and centuries of social conditioning. It seemed like a no-brainer. Like all the other milestones in the how-to-be-a-person manual.

Turns out you can’t glue-stick a life together as a child and then hop inside it when the time is right like Bert from Mary Poppins.

And so now, sitting here in 2020 typing this, I realize that I imagined a different thirty-three-year-old from the one I have actually become. This woman who has no sign of “twitching ovaries,” or fertility flutters, or random broodiness. I hold babies and, sure, they’re cute, but I give them back and don’t feel any biological shifts or urges. I see pregnancy announcements online and press the heart button but feel zero jealousy. I picture myself twenty, thirty years into the future, with silver in my hair, walking on a beach with a partner, writing in the evenings with a glass of wine, and multiple nephews and nieces visiting me in my cozy home. There might be no children of my own in my future, but why should this cause me any worry?

So why am I telling you all of this? Last month’s issue was all about

exploring different variations on adulthood and motherhood. This whole issue of .dot is dedicated to exploring what it means to be child-free, by choice, and all the other myriad ways we might decide to live our lives. We hope you love this issue as much as we do, but we realize this is the tip of the iceberg: we aren’t done talking about these issues! The decision to have kids might be one of the biggest choices we ever face, and we should be talking about this in all its complicated, nuanced depth.

Thanks as always for choosing to read .dot, and we look forward to reading your letters and tweets.

See you next month,

Editor in Chief, .dot

Olive x

Part One

“You know what gets to me? The knowing, smug smirk that so often accompanies the words: ‘You’ll change your mind.’”

Kym, 35

1

2008

“WAKE UP, OLIVE.” Bea jostled me awake gently, and I drifted from my dream into the vibrations of her deep, velvety voice. She had plonked herself down on the bed next to me, her curvaceous body cushioned softly on the mattress. Through half-opened eyes, I could make out the outline of her head of huge, tightly curled hair. I had an unused face wipe stuck to my forehead and a pounding headache. I peeled it off, and the sunlight streamed into my eyes. Bea had waltzed on in and opened my blinds again. There was no such thing as privacy in this house, and to be honest, that’s the way we liked it. The real world was a maze offering too many choices, too many narrow alleyways, too many wrong turns. Everything in this old and painted-over Victorian semidetached house felt safe. We paid bills together, we ate together, we ran errands together, we were partial to a group nap. This was our much-loved university student house, and we would be leaving here forever in a few short hours.

“Ugh?” I said, moaning. I picked up my phone with one crusty eye open and saw my ghastly reflection looking back at me on the screen. My skin was still clear and smooth, but my face looked puffier than usual, and my green eyes were blackened, like a panda’s, with eyeliner smudged all down my face. My long black hair was knotted on one side, and there were sticky drink stains along my pale arms. I sniffed. Yes, it smelled like sambuca. I had obviously attempted to clean my face with the wipe and failed miserably. I looked at the packet on the floor and realized it wasn’t even a face wipe; it was one of those kitchen wipes that you clean surfaces with.

“Have you definitely packed everything?” Bea asked, as she picked my underwear up off the floor and flung it into a carry-on bag. She lay down next to me so both of our heads were on my pillow.

“Yes. Everything is done. Just a few tiny bits left in a few drawers. Oh my god,” I croaked, “I sound like Deirdre Barlow. I must have smoked.”

“I did try and stop you. Those horrible Marlboro Reds,” Bea told me, closing her eyes and shaking her head.

“I had such a good time last night. . . .” My voice shook; I was about to cry. “I don’t want us to leave, Bea. I don’t want this chapter to be over.”

“Oh, Ol. You just need a perspective change. This isn’t the end. This is the beginning,” she said, and stroked my unwashed hair.

“I want to stay here forever.” I nuzzled into her big, comfy bosom. “It’s the end of an era. Us four, in this house together. They’ve been the best years of my life.” I put my hand on hers. She smelled of Ghost perfume. Her cashmere sweater felt so soft. I just lay there and inhaled her, my best friend. Past boyfriends had sometimes commented on how touchy-feely my friends and I were. We’d often pass out almost naked in each other’s beds. They never seemed to properly understand the intimacy of women.

The four of us had gone through the same phases over the years: like wearing all black because it seemed more chic, sporting the same gold friendship jewelry; we even got the same tattoo of a slice of pizza under our left boobs on a holiday in Australia (I know, what?). We all passed our driving test the same year, lost our virginity within a few months of each other, grew up with and quoted the same TV box sets. It definitely felt like the stars had aligned when we all ended up going to University College London to study together. We had made a pact, as a four, that UCL would be our first choice. We all wanted to go to the big city together. But we had to get the right grades at A level first, and that was going to be tough because we had spent so much of school pissing about, going to house parties with boys and smoking too much weed. But results day turned out to be one of my favorite days ever. We ripped open the envelopes together and screeched when we knew we’d be staying as a close unit for another three years. Maybe fear really is the only motivator in life.

We’ve shared all the same big milestones, the highs and the lows of new boyfriends, breakups, and family dramas. Our lives have pretty much mirrored one another’s exactly—with peaks and troughs, like lines on a graph.

“It’s been an amazing chapter, babe. But . . . it’s time.” I could tell Bea was sad, but she was also being optimistic. That’s Bea all over—the glass is always half full. The constant exhale of everything will be fine. She patted me, and then unclasped my hand, peeling herself away from me. Her presence always felt so motherly, so safe.

“I know, but let me wallow for a bit, Bea. Zeta isn’t coming to collect me for ages yet.” My older sister, Zeta, was driving down from teaching a workshop in Bristol in her battered old Mini, so she would be late. She always was—she was notorious for it. It wasn’t that she was scatty, just that she was an intensely dedicated charity volunteer, and if someone needed her for something, she would be there for them. She never felt as if she could say no, even if it meant saying no to her own family sometimes. I was glad my big sis was going to come and get me and help with my bags, but it wasn’t exactly her priority.

“C’mon. Have a shower. I’ll take that big suitcase downstairs for you,” Bea said as she rolled up her sleeves.

“Don’t take it down yet,” I said, tears glistening in my eyes.

“Ol. Look. It’s okay. I’m sad too. We all are. But c’mon, you need to get showered.”

I suddenly had a flashback to the previous night. The barman had given us all endless free shots because he fancied Cecily. Bea had ended up doing the worm on the dance floor, and Isla had stolen someone’s sombrero.

“How are you not hungover?” I heard a moan from outside the door, directed at Bea. “Are you an alien?” Cec had appeared in a T-shirt and a lace thong, sucking on a straw in a water bottle. Her blond bob was still magically intact. Her long legs had streaks of fake tan left on them.

“I am hungover. But you know me; I can’t lie in,” replied Bea, shrugging.

Cec took a running jump and landed on my bed. On top of me. Her naked bum cheek touching my leg.

“Bea, you’re so odd,” Cec said, and threw Henry, my cuddly toy, at her. It ricocheted off her chest and squeaked. “God, I feel rough.” She snuggled in under my armpit, laughing, and then said, “Olive, you reek!”

“Make room for me,” Isla croaked at the door, her dark, blunt bangs flopping over her eyes, and her glasses wonky on her freckled face. “Guys, I have the fear. Seriously, did I say or do anything weird last night?” She walked across the room, kicked off her slippers, and curled up underneath the duvet with us, spooning Cecily. Isla always gets “the fear,” ever since our sixth-form days when she got hammered at our graduation party on Bacardi Breezers and asked our only male teacher (poor Mr. Simmons) “to dance,” as if she were a character in a Jane Austen novel.

“While you’re there, Bea, can you take my suitcase down too?” Cec said, pushing her luck.

“Piss off. I’m not your mum,” Bea laughed, rolling her eyes.

“I don’t remember much from last night, you know. We really went for it, didn’t we?” said Isla. “I do have a faint memory of us breaking in to that park on the way home.” Oh my god, she was right; we had scaled the walls, and it was all Cec’s fault. Her and her wild ideas.

“I swear it was the one where Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts hung out in Notting Hill,” Cec said, trying to hold down a burp. Living in London as students regularly allowed for these strange nighttime adventures.

“You can pretend it was, love,” Bea said, lifting a heavy bag out of the room.

We had snuck into a park (could have been someone’s private garden, to be honest) and sat on a bench together, underneath some twinkling fairy lights, and reminisced about the last three years living in our special little home. We had played “Dancing in the Moonlight” by Toploader on my iPod and danced with one another. We sang like out-of-tune cats.

“Guys,” I gulped, then paused. “Can we always, always make time for each other—no matter what happens?”

Cec swung her arms around me. “You’re not getting rid of me, mate.”

“Of course, Ol, you are such a worrier!” Bea said.

Isla nodded along like a Churchill dog.

As I lay there, hungover in bed, the reality was dawning. We were moving out. Moving on from the disgusting kitchen, the mice, the creaky radiators, and the creepy landlord. There was no happier feeling than four of us in the bed. Four young sweaty bodies, entangled, feeling fragile, but excited for the future. They were my home. Home with a capital H.

There was a knock at the door. It was Bea’s boyfriend, Jeremy—we could see it was him through the frosted-glass paneling on the front door. Tall, lanky, ego-free Jeremy. Bea had never let anyone in until now; she’d had her fair share of bad boys who she’d kick to the curb when it all got a bit too real. Like Bea, Jeremy was arty, an ambitious film student who had already got an internship lined up at Working Title. They were a sweet couple, but we hardly saw him. Apparently, Jeremy never complained if she prioritized us over him, and she would only see him and stay at his house on Sunday nights, even though he had a giant TV, way better than ours. He never stayed over here either, so the majority of the time she was still ours. Maybe that was why I liked him. But now, she was leaving, and I knew there would be whispers of them moving in together. And the rest.

Olive

Olive